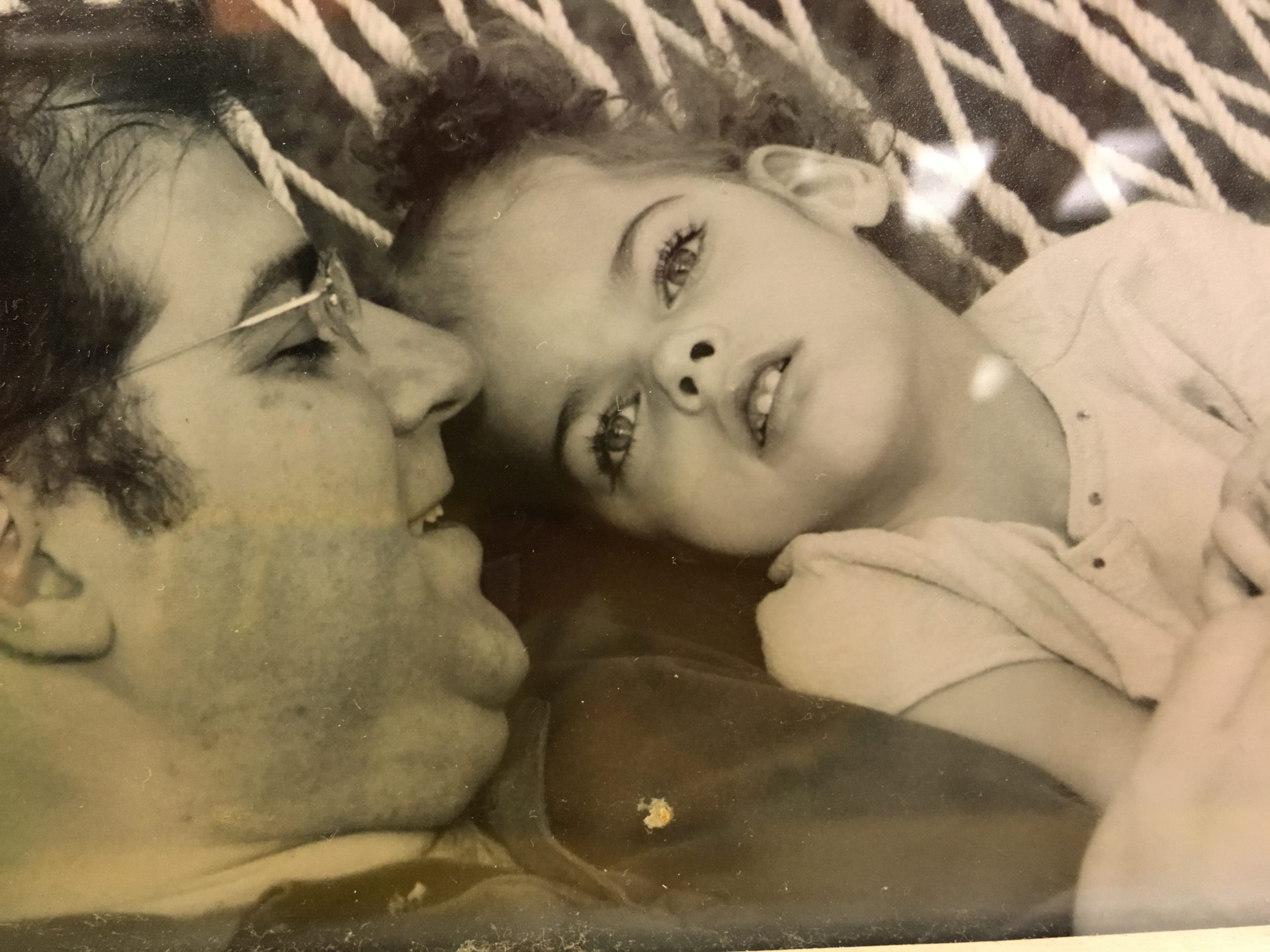

My daughter Katherine doesn’t get to do some of her favorite things. For example, she loves to pluck the leaves off a boxwood shrub that’s right up against a precarious edge in our backyard. She loves to dance to Beatles songs. And she loves to chase around her cat, Wesley, scoop him up and cuddle.

But Katherine has cerebral palsy and moves around in a power wheelchair. And, despite opening the world to her in many ways, her chair offers her no built-in protection from things like falling over ledges, painfully crashing into people or running over her beloved pets. Her love for life has always meant that we had to stay extra vigilant because of the ever-present risk of a serious accident.

For many drivers with impaired motor skills, simply getting close to one of these dangerous situations means it’s too late. There’s nothing a loved one across the room or a beeper installed on the chair can do. Katherine’s chair weighs more than 300 lbs. – over three times as much as its driver – and if she crashes, God forbid, the results can be catastrophic.

And so, therein lies my frustration: This chair that we’ve put her in to make her life better and safer, has somehow become the thing that could hurt her most.

Technology has completely disrupted the way we take taxis, use phones, shop and communicate with friends, yet it hasn’t much touched the world for people in wheelchairs. I refuse to accept that the best we can offer is simply adding a phone charger to a power wheelchair. There’s simply too little incentive for the companies that control the industry to invest when they have a captive user base that, largely, doesn’t expect much more attention. Microwaves and coffeemakers have seen more innovation over the last decade than power wheelchairs.

Technology has completely disrupted the way we take taxis, use phones, shop and communicate with friends, yet it hasn’t much touched the world for people in wheelchairs. I refuse to accept that the best we can offer is simply adding a phone charger to a power wheelchair. There’s simply too little incentive for the companies that control the industry to invest when they have a captive user base that, largely, doesn’t expect much more attention. Microwaves and coffeemakers have seen more innovation over the last decade than power wheelchairs.

I saw a toaster recently with two buttons – one saying “take a peek,” which lets you see how the bread’s doing, and one that says “a little bit more,” which lets you get the bread right where you want it. Should people like Katherine not expect their wheelchair to be smarter than a well-designed toaster?

Innovation aside, what about safety? These chairs cost as much as a car, and some collision data show that wheelchair crashes exceed the safety standards allowable for automobiles. So, what safety features do they offer? These chairs have seat belts … and not much more. When Katherine first rode around our house, it wasn’t the potential that she’d damage a wall that terrified me; it was the real risk she’d lose control and severely injure her fused spine.

I’m hardly the only parent facing those fears. According to one study, 87% of wheelchair users have had at least one tip or fall in the last three years, and another study counted more than 175,000 wheelchair accident-related ER visits every year. Some back-of-the-napkin math shows that’s more than $750,000,000 in annual medical costs for wheelchair riders – to say nothing of unquantifiable pain, grief, fear and worry.

As I got more and more frustrated by all of this, the last straw was a friend’s mother getting injured when her wheelchair – the same model Katherine drives – fell over near a boat dock and suffered traumatic injuries. For the benefit of everyone in a power wheelchair, and those who love them, I knew things had to change. And I was tired of waiting for someone else to do it.

That’s why I’m so proud to have spent the last 2.5 years working with my brother to build LUCI, a brand-new high-tech hardware and software platform that attaches to existing power wheelchairs. LUCI – which stands for Linked User Centered Intelligence (and is the name of Katherine’s favorite Beatles song) – uses cloud and sensor-fusion technologies to offer power wheelchair users unprecedented safety, stability and connectivity. Features include collision avoidance, drop-off protection, anti-tipping alerts, cloud-based communication and alerts and secure health monitoring.

In short, LUCI offers independence and mobility to my daughter and people like her.

For Katherine, testing an early version of the system has been life-changing. She’s now able to visit her beloved shrub, and we even went to a packed concert recently. We love to go to Disneyland, and next time we’ll be able to stay to the end of the fireworks, because I’m not afraid she’ll accidentally run into someone in the crowds.

When Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT, ATP, a consultant for LUCI from the University of Colorado’s Center for Inclusive Design & Engineering, saw how our system lets users follow someone or drive safely into crowds, she said: “I can hear kids laughing and how much fun they’re going to have playing with this.”

After so many years without it, having that kind of laughter at home means everything to me, and I know it will for other families too.